Am I a Product Manager or a Product Owner? Part 2

Part 2: 5 Ways to Untangle the Mess

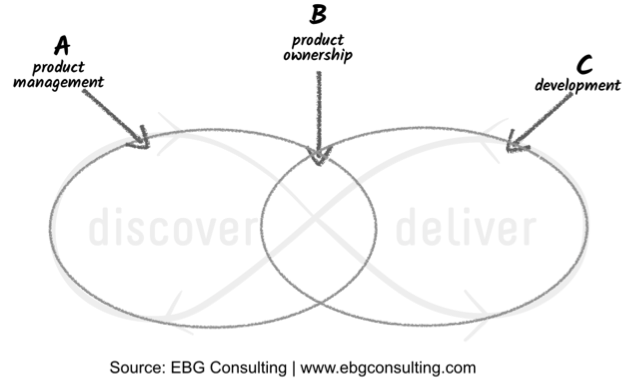

In part 1 of this blog, I outlined the confusion between what a Product Manager does and what a Product Owner does. The difference and overlaps between product management and product ownership work illustrated how activities span both strategic and tactical product management.

With the confusion of roles and titles, a team can suffer from mixed product outcomes. I find this confusion to be widespread and I propose five ways to untangle the roles and responsibilities mess to move from confusion to clarity.

The outcome of these five actions results in better collaboration and communications. Your product team focuses on what matters: building great products that customers want while meeting business goals.

Untangler #1: Clearly Identify the Product Work

Together, product and development team members explore product work to build a shared understanding of mutual interdependency and agree on who will participate in the work. Be transparent and be explicit.

By identifying that work, you’ll define the activities for product discovery and delivery. This includes customer research, hypothesis development, determining release themes, and identifying product metrics.

This conversation is an interactive activity that can follow a protocol like this:

-

- Assemble a list of product management work slips (or cards). For example, product work items include: “Build, socialize, and continually revise the product roadmap” or “Decide on backlog items for the next iteration.”

- Gather product and development team members in a shared space. Select a work item, show the item, and read it out loud.

- Ask, “Does anyone have a question about what that work entails? And if so, please clarify.”

- Ask, “Does this work apply to our product’s lifecycle, market, industry, and team culture?” In my experience, this challenge encourages a lot of discussions.

- Go deeper. Explore where that work item belongs along the continuum of strategic and tactical (and discovery and delivery). Using a piece of poster paper placed on a table, draw the Venn diagram I shared in Part 1, modified for this activity.

6. Openly discuss the placement of work items in the Venn diagram.

7. Repeat the steps above until all work items have been discussed.

Product and development people engage in deep and useful conversations every time I’ve facilitated an activity like this. The team deepens their understanding of their mutual reliance on each other to be successful. Sometimes, it is a simple matter of improving broken communication.

Untangler #2: Clarify Decision-Making Rules

When roles are confusing, it impacts the ability to make decisions. What I’ve found is that the team does not understand decisions rules. Simply put, product people need to Decide How to Decide.

There are many decisions in product work that take place throughout a product’s lifecycle. This includes changing or abandoning product ideas based on feedback, defining acceptance criteria for items to be delivered, determining what technical debt to invest in, defining value metrics for the product, prioritizing backlog items and identifying which customer or market segment to focus on. As a product person—whatever your job title is—clarifying your decision rules helps you use participatory decisions, rely more on others, and reduce communication friction.

Not all decision rules need to be participatory, and yet, participatory decisions are best for any high stake decision. We know this intuitively. Actively engaging the people who have to carry out a decision always yields more sustainable outcomes. [1]

Clarifying decision rules is more complicated when you have a large, complex product, a portfolio of products, or multiple levels of product management. Your organization may use a variety of job titles like:

- VP of Product with Product Managers reporting to her

- Chief Product Owner with oversight over Product Owners

- Senior Product Manager overseeing a team of Product Managers and Technical Product Managers

- Product Manager and Area Product Managers

In those situations, clarify who is the ultimate decision maker. Often, the VP of Product makes decisions on product strategy. At the same time, decisions that are more tactical in nature, such as deciding product hypotheses to try as part of ongoing discovery can rest with the Product Manager. Gain buy-in with the product team first and then share it with the larger organization.

Reconsider using consensus as a decision rule. When the right people participate, a consensus rule can indeed lead to a sustainable decision. However, it takes longer to reach consensus. And, overuse of consensus can disempower the authority of the ultimate decision maker. If you still choose consensus, without a way to test for agreement, people wander into a fog of uncertainty.

An example is a large organization I worked with that had a Product Counsel responsible for making decisions on product direction and investments. The Counsel chair was the Head of Product. Without explicitly saying how they would Decide How to Decide, committee members assumed they all needed to agree on decisions. This ultimately defaulted to a consensus approach to decision making.

They had to decide whether to refocus the product on a new market segment or not. Based on the ebb and flow of the team’s conversation, the hope was that a decision would simply fall out. Worse, they had never explicitly clarified their decision-making rule for this important decision—let alone how they would verify they had reached a final decision.

The next week, the Head of Product made a large expenditure for external market research and began rallying staff from the strategy team to work on their approach to this new segment. Product Council members were aghast. They hadn’t agreed, yet the Head of Product assumed they had.

This disconnect, unfortunately, triggered a major loss of trust and it took many weeks to repair the fallout. Some Product Counsel members felt reticent to fully trust the product group, stifling honest communications for months to come.

The preventative fix could have been simple. Clarify the decision rule and use a simple tool (like my adaption of the gradient of agreement) to explicitly validate any agreement. This approach takes less than a minute to use.

Untangler #3: Increase the Degree of Freedom

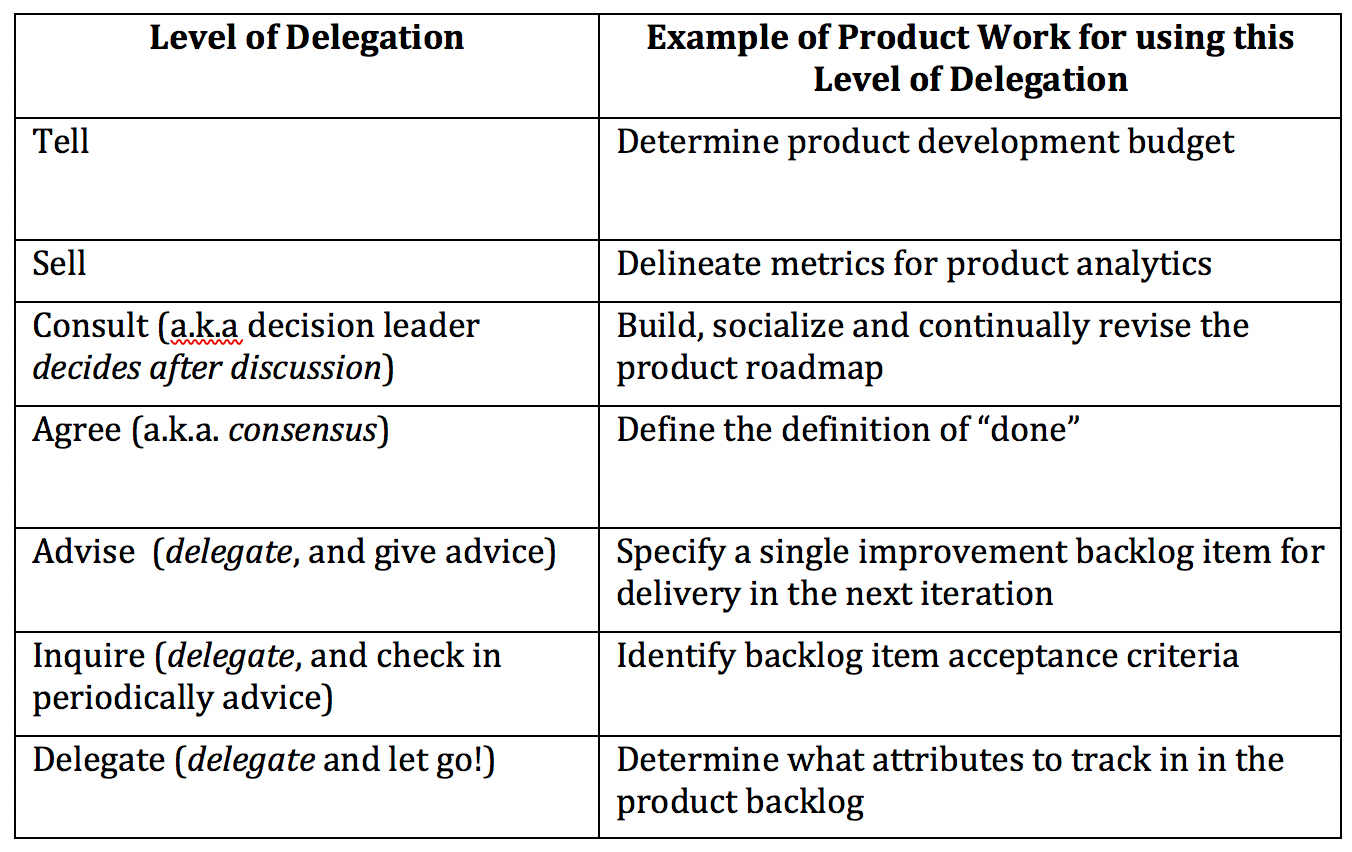

Where possible, progressively increase the degree of freedom for product decisions. As the product development team gains expertise in the product, market, and strategy, delegate some product decisions to them. I have found that progressive empowerment works best.

Let’s say your decision rule for determining the theme for your monthly release is “decision leader decides after discussion.” This means that after seeking the team’s input, you ultimately decide the theme. This sounds reasonable.

However, imagine that you have a great product development team. They grok the product vision, can truly empathize with customers, and understand how the product roadmap aligns with the company strategy. And you? Well, you are very busy with customer and market research as well as engaging executives and support staff in product roadmapping. In this scenario, your team is ready for you to shift toward a more consultative decision-making rule. After providing some guidance, you delegate the decision on the theme to the product development team.

One product manager I worked with retained final UI design and layout decision-making authority. The team needed her approval for new features before they could proceed. In time, the team became adept at conducting usability tests and iterating wonderful UI designs. Customer feedback was positive. I suggested she shift to delegating decision making authority for the UI design to the team, and simply inquire about their progress by looking at mockups and asking how the testing was going. Needless to say, this helped the team’s flow and removed one more burden from her plate.

This delegation doesn’t come easy and I like using the seven levels of delegation as a tool. This approach encourages greater degrees of decision-making freedom among product and development team members. [2, 3] I often combine the degree of delegation freedom with the prior two recommendations, by mixing in the delegation poker activity: [4]

As you would expect, shifting from a consultative decision-making style toward one with more delegation depends on the nature of the decision and the strength of the development team. A strategic decision, such as determining the launch plan for a major feature will need to stay with you, the product leader.

A development team with strong technical practices, ability to deploy on demand, rich domain experience, and a keen focus on outcomes will falter without greater autonomy. You increase trust, build competence, and inspire confidence by affording your development team a great degree of freedom for product-related decisions.

Untangler #4: Be Smart About Scaling Large Products

Be smart about scaling large products, retaining highly cohesive, loosely coupled product areas with a single product person. Organizations supporting large, complex products struggle with scaling the work of product management. A single person responsible for the whole picture usually leads to better product decisions. How can one person manage all the strategic, high-level work while being expected to lead the tactical, delivery work?

Scrum calls for the product owner role to act as the manager of the product backlog. To do that well, you need to understand the strategy and roadmap. Conversely, to steer the product vision, guide product roadmapping, and research the market and customers, you benefit by understanding technical feasibility and studying validation data from releases. Can one person really do it all?

I don’t recommend splitting the strategic and tactical work among different people. The product person is drawn into the tactical work at the expense of the strategic work. The pressure of the tactical “now” always overrules making time for hunting for future, strategic value.

If you must slice the product work due to sheer size of the product, do so vertically by product area, not by the type of work.

A good model is provided in Large Scale Scrum (LeSS), which partitions product management for a large product into requirement areas. [5] Product managers for a product area (LeSS calls them by the Scrum-ish role name, Area Product Owner), have decision making authority for a customer-centric portion of the product and collaborate with other area product owners for the product. [6] In this approach, there is a single product backlog with views into each product area. [7] This distribution of responsibilities enables the product person to manage a set of highly cohesive and interdependent strategic and tactical work, but for a smaller slice of a very large product.

Development teams need to evolve their domain knowledge and build relationships so they can independently hunt down answers to tactical questions. This helps their product leader to not get sucked into “story hell.” Product people acting as facilitators, don’t have to know all of the answers. They introduce their savvy development team to domain experts. That way, the team can ask specific questions on business rules and specific data fields, for example, without relying on the presence of the product person. This approach enables the team to build their own relationships with people they can have Structured Conversations with so they can build the best product possible.

Untangler #5: Pollinate Cross-Learning

Despite the widespread adoption of Scrum, the broader agile community has been slow in cross-pollinating with the product management community. Agilists are great at improving the delivery engine but are less aware of the complex and rich discipline that is product management.

Conversely, some in the product management community are reluctant to pay attention to agile happenings. This may be due to the perception that the agile community has an incomplete appreciation of product management. The cynical view is that Scrum focuses only on tactical, backlog management work, turning product people into backlog jockeys.

If agilists are foggy about product “value” or are more focused on process metrics (such as velocity) over product outcomes, they lose credibility in the eyes of product people.

Let’s do better at cross-fertilizing our knowledge and experience. Agilists can learn about product management through books, blogs, conferences, hackathons, internal lunch and learns, meetups, lean coffees, World Café, and product summit events. Conversely, product people can learn more about agile principles and practices through those same means.

I teamed up with Vanessa Ferranto several years ago to form a community called Agile Product Open, with an annual conference and meetups. The Agile Alliance sponsors the Agile Product Management Initiative striving to improve product management through agile principles and practices—and visa versa (I serve as volunteer director).

Others use guilds, Open Space events, and communities of practices for internal sharing. Brainstorm with your team on what you can do.

Tame It!

The confusion in product titles and roles is harmful and obfuscates the goals of building great products and healthy, productive product, development teams.

You can remove any perception of title tyranny by being transparent about the work and clarifying decision-making authority. Increasing decision-making freedom to product development teams, where appropriate, builds stronger teams. Thoughtful scaling of product management encourages strong product focus. Proactively seeking to improve cross-discipline knowledge helps mitigate misunderstandings among product and development people.

I hope these five “untangles” will free your energies toward building and sustaining better products and better teams.

References

- Nutt, Paul. Why Decisions Fail: Avoiding the Blunders and Traps that Lead to Debacles. 2002. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Chapman, Alan “Delegating to a Group: Tannebaum and Schmidt Continuum”.” Business Balls. https://www.businessballs.com/team-management/tannenbaum-and-schmidt-continuum%C2%A0delegating-to-a-group-and-developing-your-team-113.

- Appelo, Jurgen. “Leading Agile Developers: The Seven Levels of Authority (Part 2).” InformIT. February 2, 2011. http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=1675546&seqNum=3.

- Appelo, Jurgen. “Delegation Poker”. Management 3.0. https://management30.com/product/delegation-poker.

- The LeSS Company. “Requirement Area”. Large Scale Scrum website. 2014-2018. https://less.works/less/less-huge/requirement-areas.html.

- The LeSS Company. “Area Product Owner”. Large Scale Scrum website. 2014-2018. https://less.works/less/less-huge/area-product-owner.html.

- The LeSS Company. “Area Product Backlog”. Large Scale Scrum website. 2014-2018. https://less.works/less/less-huge/area-product-backlog.html.

Additional Reading

To learn more about product management and product ownership, I recommend:

Cagan, Marty. “Product Manager vs. Product Owner Revisited”. December 13, 2016. https://svpg.com/product-manager-vs-product-owner-revisited.

Mironov, Rich. “We Don’t Hire Product Owners Here”. June 11, 2014. https://www.mironov.com/pohire.

Pichler, Roman. “ Product Manager vs. Product Owner”. March 14, 2017.

https://www.romanpichler.com/blog/product-manager-vs-product-owner.

Perri, Melissa. “Product Manager vs. Product Owner”. June 29, 2017. https://melissaperri.com/blog/2017/06/29/product-manager-vs-product-owner.

Leave a Reply